Early this year, we received the wonderful news that Naku, Nakuu, Nakuuu! (written by Nanoy Rafael and Sergio Bumatay III) won IBBY-Sweden’s Peter Pan Prize. We returned last week from an eventful Gothenburg Book Fair, where the Prize was officially awarded to Nanoy and, to receive the prize on Sergio’s behalf, Isko. We will be posting updates and pictures from that event here on our blog, and on our Facebook page, so watch out for those! For now, we are happy to share with you an article published in Opsis barnkultur, a Swedish magazine dedicated to children’s literature. This article talks about our local children’s literature scene, in light of a Philippine publication winning the Peter Pan Prize.

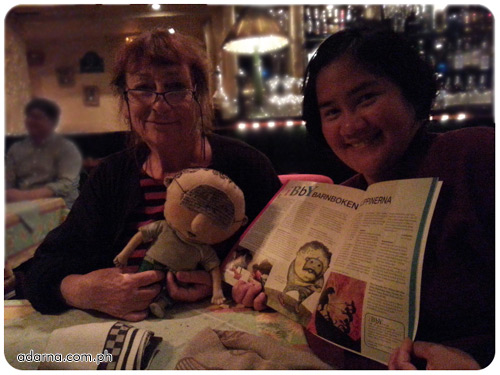

Isko (from Naku, Nakuu, Nakuuu!) with Lakambini Sitoy,

the Denmark-based Filipino novelist who wrote the article,

and Ulla Forsén, IBBY-Sweden VP and translator of the text into Swedish.

Philippine children’s literature industry

by Lakambini Sitoy

THE stereotypical view of Philippine life is of a hand-to-mouth existence, where people have neither the resources to buy books, nor the mental space to read. This is untrue: the country has a flourishing book industry, with a dynamic children’s book industry.

There are over 10 publishing houses specializing in, or with a branch dedicated to, children’s books. These include Adarna House, which put out Naku naku nakuuu!, Tahanan Books, Lampara, Anvil, the University of the Philippines Press, and Giraffe. On certain occasions, private organizations, of commercial, religious or charitable orientation, may publish children’s books as well. Their collective output encompasses picture books in full color, storybooks with illustrations in either full color or black and white, novels and chapter-books for young adults, anthologies, and even stationery featuring the artwork/illustrations.

Myths, legends and fables remain a popular subject, as do personified animal stories and myth-like tales written by contemporary authors. Ever popular are series featuring national heroes and statements, most connected with the independence movement of 1898. At least one publishing house, Lampara, puts out abridged versions of British classics, in English, with new illustrations. Yet many titles deal with everyday life and its conundrums and rites of passage, and a few address difficult topics like death, child abuse, bullying, parents who must work abroad, and indigenous peoples.

The books range in price from about P70 for storybooks, to P600 and even more. P70 will buy a meal and soft drink at a fast-food franchise, or a flimsy t-shirt, or some 5 minutes talk time on a prepaid mobile phone card. The minimum wage for office workers in the Metro Manila area is about P450 per day; however, Philippine children’s books are usually purchased by professionals who earn much more than this, i.e. with dual middle-class to upper-middle class incomes.

Incentives for writers come in the form of contests, such as the annual Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards, which has a “story for children” category in both English and Filipino, and the Philippine Board on Books for Young People’s Salanga Prize. Universities with creative writing programs frequently offer a course on writing for children. Fine Arts or design students at university may specialize in children’s book illustration, submitting a mock-up of a book as thesis. The PBBY also awards an annual Alcala Illustrator’s Prize, and the National Children’s Book Awards (with the National Book Development Board). Ang INK is an organization of illustrators for children that puts up local exhibits and is active on-line. Illustrators nowadays tend to be young, well-trained and happy to experiment with new media and styles.

The Philippine government has also offered publishers incentives, such as the Library Hub, which has purchased hundreds of thousands of books from local publishers, for the use of children all over the country, including those residing in remote barrios (villages).

Language issues

In a country with two official languages — English and Filipino — as well as several regional languages, bilingualism (and tri- and multi-lingualism) is the rule rather than the exception.

It is not unusual to find picture books and storybooks with the text in both languages, printed next to each other, as with Adarna House’s titles — whatever the language of the original text, it appears with a translation. Otherwise, the text may be in English or Filipino. Most mysteries or chapter books are written and published in English, as are storybooks with longer text. Rare is the trilingual picture book, or for that matter, text in the regional languages such as Cebuano or Hiligaynon.

There is a sense that Filipino, and the Tagalog language on which it is based, is a language under threat and must be nurtured by providing literary models of the best possible sort. It is also viewed as the first language of many Filipinos and thus, the best way to reach them at a young age. Yet English is privileged in the country, owing to its associations with cosmopolitanism and better job opportunities abroad as well as at home.

Reni Roxas, publisher of Tahanan Books, explains why the house began, some five years ago, to introduce Filipino or bilingual titles into what had been an all-English inventory: “First, the demand for vernacular books is fueled by the quest of a developing country still in search of itself. Second, Filipino families living abroad are enjoying renewed interest in the Filipino language. … Filipino-Americans who grew up in households where learning the mother tongue was de-prioritized in favor of cultural assimilation into the host country, now regret not having learned the language of their parents. They now want to teach Filipino to their children.”

Competition

The greater challenge, however, is how to grab a share of a market dominated by foreign books, which are readily available brand new all over the country, as well as from secondhand bookstores/ shops. In the latter, stocked mostly with rapidly-replenished inventory from the United States, books for children can be had for as little as 10 pesos. The ready availability of material at every price point is good for Filipino children’s reading habits, but puts local publishers at a disadvantage, with parents preferring to put their money on international super-sellers like the Harry Potter series, or Disney.

As with the rest of the world, Filipino children devote considerable attention to television, computers, mobile phones and, among higher income families, newer digital devices such as iPads or smart phones. These are valued for the entertainment they provide and as learning tools that augment what goes on in the classroom.

Even without the competition from electronic devices, the children’s book industry must reckon with the priority given to textbooks in a family’s budget. This is not surprising, in a culture that puts a premium on education, and where enrollment at the better schools is neither free, nor even subsidized.

Cultural and moral imperatives

“In the Philippines, publishing children’s books is more of a public service rather than a lucrative business,” says Vanessa Estares, Marketing Officer of Adarna House. “You almost only make enough to produce the next batch of books and you do it because you know that there is a need for books that will instill pride and love of language, and culture, and country in Filipino children.”

Adarna is typical in its view of its work as a kind of advocacy, one which demands that books be made affordable, and thereby accessible, to as many children as possible. In addition, according to Estares, their material — which has dealt with the tough subjects that “some publishers might not even consider” — stems from “the highest respect for the child’s ability to understand certain issues, with guidance from a parent reading a book to them.” Estares notes that their sales are influenced by the preference among parents and teachers for material that promotes moral and pedagogical values.

These preferences, of course, affect publishers across-the-board, and in turn have an impact on the themes and treatment of the material. As mentioned, numerous titles throughout the industry affirm a sense of nationalism and the legacy of indigenous storytelling. While there is considerably creativity, innovation and experimentation nowadays, children’s books throughout the 30-40 year history of the industry, have had a harmonious look, an idealized prettiness. In this context, the illustrations in Naku, nakuu, nakuuu! are different, and doubtless a preview of the future.

_____________________________

Thank you to Opsis barnkultur, author Lakambini Sitoy, and translator Ulla Forsén for the permission to post this article on our blog. The article first appeared in Swedish, on page 56 of Opsis barnkultur issue Nr2 2013.